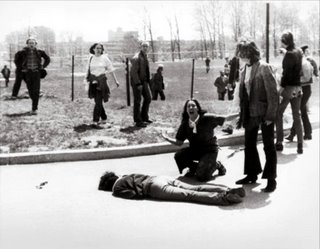

Muse's entry on this blog about why the anti-war movement isn't getting more press prompt this portion of an encyclopedic history of the war in total. For purposes of understanding part of the answer to Muse's query, it helps to understand the one most recent example we have. There are so many common areas of involvement between the two wars, it expands anyone's knowledge to take a look at the events that drove the conflict beginning even well before the Truman administration. That history can be googled easily for those who wish to widen their wisdom. Meanwhile, the following is a partial account of opposition to the Viet Nam Conflict, and outlines why and how we were ultimately able to extract ourselves from that war. Coincidentally, violent opposition to the war in the form of police action against protesters, and the riots caused by authoritative actions finally brought the media coverage that helped end the war, and was also instrumental in the civil rights movement to gain visibility. The media was instrumental at the time in keeping American citizens informed, and unlike today, there was much less repression of a free press. Photojournalism of the kind you see at the beginning of this post wasn't hindered or censured. (The famous picture of the young girl screaming in anguish for the murdered Kent State student protester, killed by the National Guard or police) Need we be reminded once again, "If we do not know history, we are doomed to repeat it"...

Muse's entry on this blog about why the anti-war movement isn't getting more press prompt this portion of an encyclopedic history of the war in total. For purposes of understanding part of the answer to Muse's query, it helps to understand the one most recent example we have. There are so many common areas of involvement between the two wars, it expands anyone's knowledge to take a look at the events that drove the conflict beginning even well before the Truman administration. That history can be googled easily for those who wish to widen their wisdom. Meanwhile, the following is a partial account of opposition to the Viet Nam Conflict, and outlines why and how we were ultimately able to extract ourselves from that war. Coincidentally, violent opposition to the war in the form of police action against protesters, and the riots caused by authoritative actions finally brought the media coverage that helped end the war, and was also instrumental in the civil rights movement to gain visibility. The media was instrumental at the time in keeping American citizens informed, and unlike today, there was much less repression of a free press. Photojournalism of the kind you see at the beginning of this post wasn't hindered or censured. (The famous picture of the young girl screaming in anguish for the murdered Kent State student protester, killed by the National Guard or police) Need we be reminded once again, "If we do not know history, we are doomed to repeat it"... Opposition to the war

Small-scale opposition to the war began in 1964 on college campuses. This was happening during a time of unprecedented leftist student activism, and of the arrival at college age of the demographically significant Baby Boomers.

Conscription in the United States had existed continually (except for a lapse during 1947-1948) since 1940, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt instituted the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. Though conscription remained at a low level through much of the Cold War, it increased dramatically in 1964 to provide troops for the Vietnam Conflict. Formal protests against the draft began on October 15, 1965, when the student-run National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam staged the first public burning of a draft card in the United States.

Abuses in the Selective Service System were one cause of protest, as local "draft boards" had wide latitude to decide who should be drafted and who should be granted "deferments" which usually meant escaping military service. The first draft lottery since World War II in the United States was held on December 1, 1969, based on a potential draftee's date of birth. While this had the effect of giving relative certainty to young men as to their chances of being drafted, it also had the effect of dividing those eligible youth who engaged in war protest, as noted by The New York Times in a December 8, 1969 article: "Draft Lottery Changes Views of Eligibles."

Statistical analysis indicated that the methodology of the lotteries unintentionally disadvantaged men with late year birthdays. This issue was treated at length in a January 4, 1970, New York Times article titled "Statisticians Charge Draft Lottery Was Not Random".

U.S. public opinion became polarized by the war. Many supporters of the war argued for what was known as the Domino Theory, which held that if the South fell to communist guerillas, other nations, primarily in Southeast Asia, would succumb like falling dominoes. Military critics of the war pointed out that the conflict was political and that the military mission lacked clear objectives. Civilian critics of the war argued that the government of South Vietnam lacked political legitimacy and that support for the war was immoral. Some anti-war activists were themselves Vietnam Veterans, as evidenced by the organization Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Some of the U.S. citizens opposed to the Vietnam War stressed their support for ordinary Vietnamese civilians struck by a war beyond their influence. President Johnson's undersecretary of state, George Ball, was one of the lone voices in his administration advising against war in Vietnam.

The growing anti-war movement alarmed many in the U.S. government. On August 16, 1966 the House Un-American Activities Committee began investigations of U.S. citizens who were suspected of aiding the NLF. Anti-war demonstrators disrupted the meeting and 50 were arrested.

On February 1, 1968, a suspected NLF officer was captured near the site of a ditch holding the bodies of as many as 34 police and their relatives, some of whom were the families of General Nguy n Ng c Loan's deputy and close friend. General Loan, a South Vietnamese National Police Chief, summarily shot the suspect in the head on a public street in front of journalists. The execution was filmed and photographed and provided another iconic image that helped sway public opinion in the United States against the war.

In Australia, resistance to the war was at first very limited, although the Australian Labor Party (in opposition for most of the period) steadfastly opposed conscription. However anti-war sentiment escalated rapidly in the late 1960s as more and more Australian soldiers were killed in battle. Growing public unease about the death toll was fueled by a series of highly-publicised arrests of conscientious objectors, and exacerbated by the shocking revelations of atrocities against Vietnamese civilians, leading to a rapid increase in domestic opposition to the war between 1967 and 1970. The Moratorium marches, held in major Australian cities to coincide with the marches in the USA, were among the largest public gatherings ever seen in Australia up to that time, with over 200,000 people taking to the streets in Melbourne alone.

On October 15, 1969, hundreds of thousands of people took part in National Moratorium antiwar demonstrations across the United States. A second round of "Moratorium" demonstrations was held on November 15, 1969.

On April 22, 1971, John Kerry became the first Vietnam veteran to testify before Congress about the war, when he appeared before a Senate committee hearing on proposals relating to ending the war. He spoke for nearly two hours with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in what has been named the Fulbright Hearing, after the Chairman of the proceedings, Senator J. William Fulbright. Kerry presented the conclusions of the Winter Soldier Investigation, in which veterans claimed to have personally committed or witnessed war crimes.

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson began to seek a second term. A member of his own party, Eugene McCarthy, ran against him for the nomination on an antiwar platform. McCarthy lost by just 300 votes to Johnson in the first primary election in New Hampshire. The resulting blow to the Johnson campaign, taken together with other factors, led the President to make a surprise announcement in a March 31 televised speech that he was pulling out of the race. He also announced the initiation of the Paris Peace Talks with Vietnam in that speech. Then, on August 4, 1969, U.S. representative Henry Kissinger and North Vietnamese representative Xuan Thuy began secret peace negotiations at the apartment of French intermediary Jean Sainteny in Paris. This set of negotiations failed, however, prior to the 1972 North Vietnamese offensive.

On January 21, 1977, U.S. President Jimmy Carter pardoned nearly all Vietnam War draft evaders.

0 comments:

Post a Comment